Semantics

- Musleh Saadi

- Aug 9

- 6 min read

Updated: Aug 11

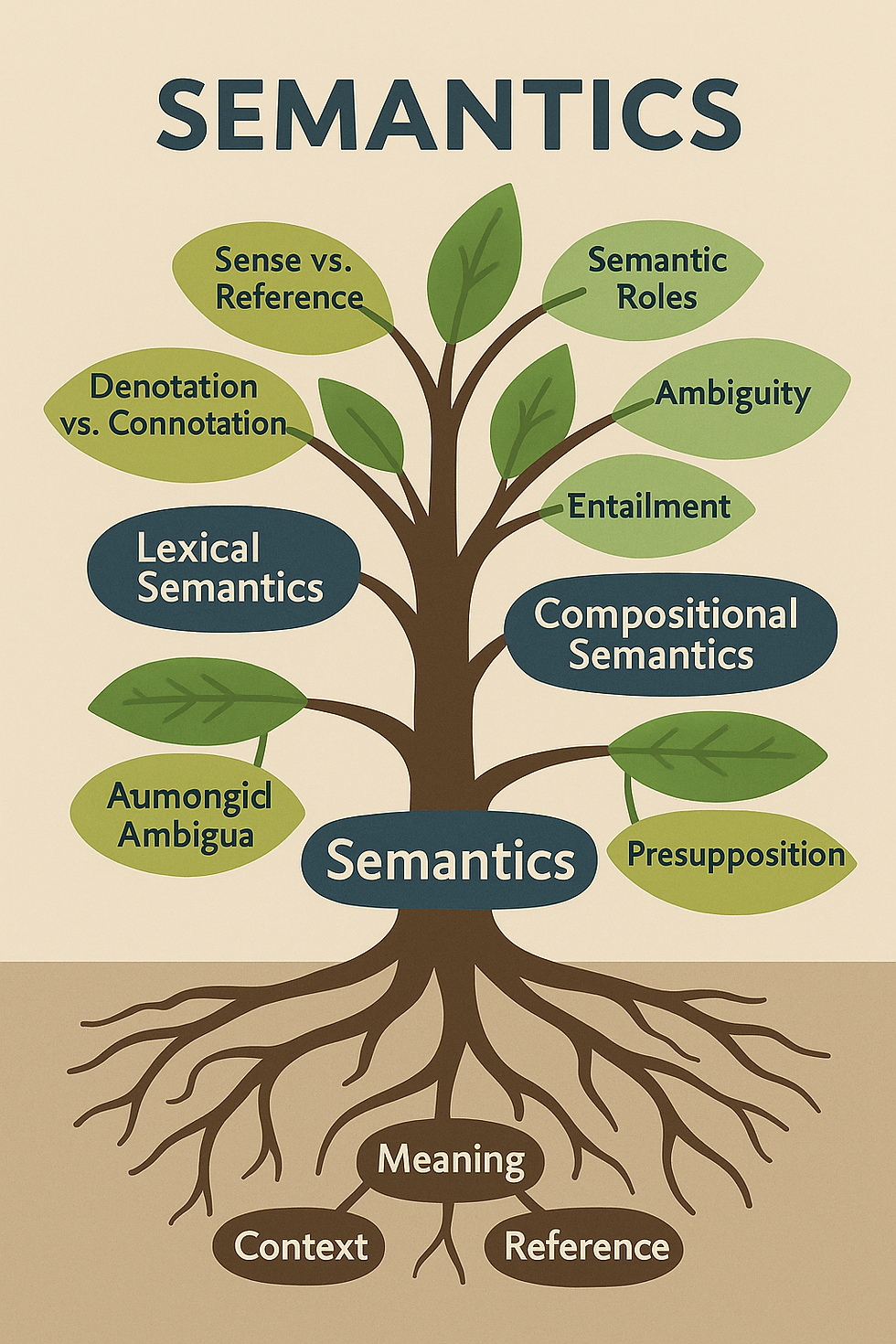

The book Semantics offers a systematic exploration of how meaning is constructed, interpreted, and analyzed in language. It introduces readers to core semantic concepts such as sense and reference, denotation and connotation, and the distinction between literal and figurative meanings. The text moves from foundational definitions to complex theories, such as componential analysis, truth-conditional semantics, and cognitive semantics. By incorporating examples from multiple languages, the author ensures that meaning is contextualized beyond English alone, illustrating how cultural and linguistic diversity affects semantic interpretation.

A central focus of the book is the relationship between words and the world they describe, a relationship articulated through reference (linking expressions to real-world entities) and sense (the conceptual content of expressions). For example, the terms “morning star” and “evening star” differ in sense but share the same referent: the planet Venus. The book also highlights semantic fields and lexical relations such as synonymy, antonymy, hyponymy, and polysemy, using practical examples like “buy” vs. “purchase” (synonymy) and “dog” as a hyponym of “animal.” The discussion emphasizes that meaning is both a cognitive construct and a social phenomenon. The book also examines how meaning interacts with context through deixis, implicature, and presupposition. For instance, deictic expressions such as “here,” “there,” “this,” and “that” cannot be fully understood without knowing the speaker’s location and time of utterance. Grice’s Cooperative Principle is introduced to explain how speakers imply more than they explicitly say, as in the conversational implicature: “It’s cold in here” functioning as a request to close the window. By blending semantic theory with pragmatic considerations, the text shows that meaning is not fixed but dynamically shaped by speaker intention and listener interpretation. Beyond theory, the book applies semantic analysis to real-world domains, including translation, artificial intelligence, lexicography, and discourse analysis. For example, it explores how ambiguity in natural language poses challenges for machine translation systems, or how lexicographers resolve polysemy when creating dictionary entries. The concluding sections stress that semantic awareness deepens understanding in both everyday communication and academic research. While the book is comprehensive, its depth in theoretical detail may challenge beginners, making it most suitable for advanced undergraduates or linguistics students seeking to refine their analytical skills.

Semantics operates on two levels: the meanings of individual words (lexical semantics) and the meanings of sentences and phrases (sentential semantics). Lexical semantics involves understanding what each word stands for, while sentential semantics focuses on how these words come together to express larger ideas. For example, the sentence “The child is playing with a dog” relies on both the lexical meaning of dog and the sentential meaning, which tells us what is happening in the interaction between the child and the animal.

Semantic Properties and Features

One of the key concepts in semantics is the idea of semantic properties. These properties are used to describe the inherent features of words, helping to explain why certain words can be grouped together. For instance, the words woman, aunt, and hen share the semantic property of female, while boy, man, and bull share the property of male. By examining these shared properties, we can understand how the meanings of different words relate to one another.

These properties also extend into finer distinctions. Take the words puppy and dog. Both share the semantic property of being canine, but the word puppy also carries the additional property of young, distinguishing it from the more general term dog. Understanding these distinctions allows speakers to be precise in their communication, tailoring their language to convey exactly what they mean.

-Nyms: Exploring Word Relationships

Words rarely exist in isolation; they frequently have intricate relationships with other words. One way to explore these relationships is through the various types of -nyms: synonyms, antonyms, homonyms, and hyponyms, among others. Each type of relationship sheds light on how words are connected and how they interact within the system of language.

Synonyms are words with similar meanings, such as begin and start, or big and large. Although no two words have exactly the same meaning in every context, synonyms provide a way for speakers to express similar ideas in different ways.

Antonyms represent opposites. The words hot and cold, for example, represent two ends of a temperature scale. Antonyms can be either gradable (like big and small) or complementary (like dead and alive), depending on whether the words allow for degrees of comparison.

Homonyms are words that sound the same but have different meanings, such as bear (the animal) and bear (to carry). Homonyms can create ambiguity in language, leading to misunderstandings if the context isn’t clear.

Hyponyms express a relationship between a general term and a more specific one. For example, cat is a hyponym of animal, and poodle is a hyponym of dog. This hierarchical relationship helps us classify and organise the meanings of words within broader categories.

Understanding these semantic relationships is key to mastering a language, as they allow us to expand our vocabulary and communicate more effectively.

Sense, Reference, and Propositions

Another central concept in semantics is the distinction between sense and reference. The sense of a word refers to its inherent meaning — the mental concept we associate with it — while the reference is the actual object or entity in the world that the word refers to. For example, the word dog has a sense that involves characteristics like being a mammal, having four legs, and barking. The reference of dog could be any specific dog, such as one you see in the park.

Sentences, too, have meaning, which is expressed through propositions. A proposition is the core meaning of a sentence — the statement it expresses. For instance, the sentence “The cat is on the mat” expresses a proposition that can either be true or false, depending on whether the situation described matches the real world. If the cat is, indeed, on the mat, the proposition is true. If not, it is false.

Truth Conditions and Meaning

The relationship between a proposition and the world gives rise to the concept of truth conditions. To understand whether a proposition is true, we must first know the conditions under which it would be true. For example, the sentence “The sky is blue” is true only if the sky is actually blue at the time of speaking. Truth conditions allow us to evaluate the accuracy of statements and play a crucial role in logical reasoning.

Sentences that share the same truth conditions are considered paraphrases. For example, “The police arrested the burglar” and “The burglar was arrested by the police” are paraphrases because they express the same proposition, despite having different structures. This concept helps linguists understand how meaning can be preserved even when the form of a sentence changes.

Ambiguity in Language

Ambiguity arises when a word or sentence has more than one possible meaning. Lexical ambiguity occurs when a single word can refer to multiple things, like bat, which could mean either an animal or a piece of sports equipment. Structural ambiguity, on the other hand, occurs when the structure of a sentence allows for multiple interpretations. Consider the sentence “I saw the man with the telescope.” This could mean either that the speaker used a telescope to see the man, or that the man they saw had a telescope.

Ambiguity is a natural part of language, but it can also lead to misunderstandings. Semantics helps us navigate these ambiguities by providing tools to disambiguate meanings based on context, word order, and other clues.

Thematic Roles and Sentence Structure

In any sentence, words take on specific thematic roles that describe their relationship to the action or event described by the verb. Common thematic roles include the agent (the doer of the action), the theme (the entity being acted upon), and the goal (the endpoint of the action).

For example, in the sentence “The woman gave the book to the child,” the thematic roles are as follows:

Agent: The woman (the one performing the action)

Theme: The book (the object being transferred)

Goal: The child (the recipient of the book)

Thematic roles help us understand who is doing what in a sentence and provide a deeper layer of meaning beyond just the surface structure of the words.

Conclusion

Semantics is a vital component of language, guiding how we interpret words, sentences, and larger meanings. Studying semantics allows us to better understand the relationships between words, the structures that shape sentence meaning, and how language reflects the world around us. By exploring the intricacies of meaning, we uncover the cognitive processes that enable us to communicate with precision, nuance, and creativity.

Further Reading:

Lyons, J. (1995). Linguistic Semantics: An Introduction. Cambridge University Press. This book offers a comprehensive introduction to the study of meaning in language, covering both theoretical frameworks and practical applications. Readers interested in understanding how language reflects thought and culture will find Lyons’ clear explanations and examples essential for grasping complex semantic concepts.

Saeed, J. I. (2003). Semantics. Wiley-Blackwell. Saeed’s Semantics provides an accessible yet detailed overview of key topics in semantic theory, including word meaning, sentence meaning, and the relationship between language and context. With its engaging writing style and rich examples, this book is perfect for both beginners and more advanced students wanting a deep dive into the workings of meaning.

Cruse, D. A. (2011). Meaning in Language: An Introduction to Semantics and Pragmatics. Oxford University Press. This book delves into the relationship between meaning and context, exploring how semantics and pragmatics work together to shape communication. Cruse’s text is a must-read for anyone interested in language philosophy, making complex ideas clear through thoughtful analysis and practical examples.

Good jb 👍

Amazing

Impressive 👏